Como no me alcanza cuando me dicen que no hay cura, que es normal y que no se puede hacer nada, este es mi minúsculo aporte. De la misma forma estoy abierto a cualquier sugerencia, comentario, recomendación etc. etc.…

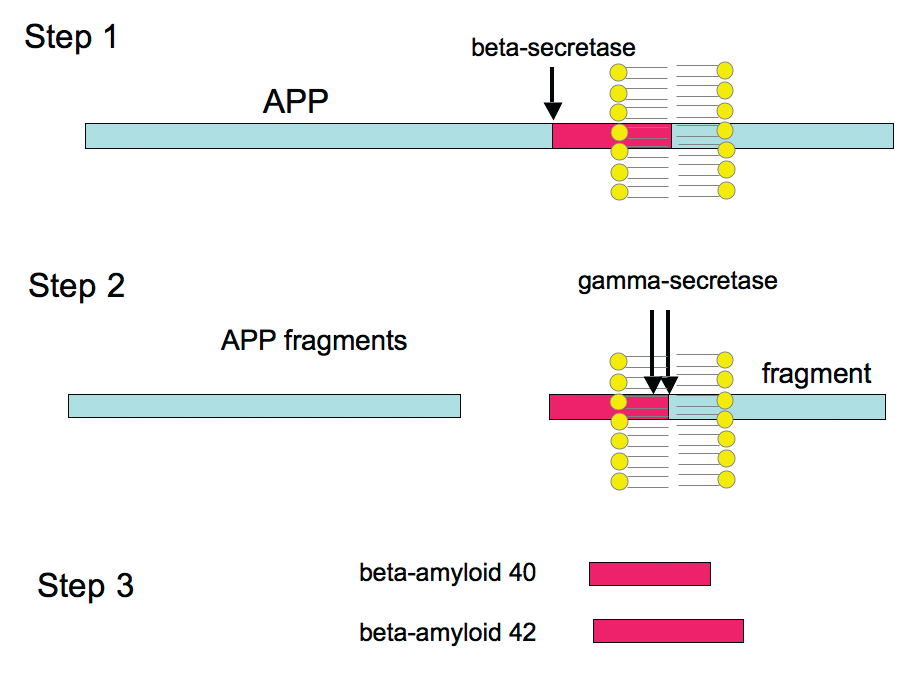

Beta-amyloid is believed to cause most of the degenerative brain changes underlying Alzheimer’s disease. Scientists at the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at The Rockefeller University have been pursing which types of beta-amyloid protein may be responsible for theses degenerative brain changes, as well as how each disrupts the transmission of nerve impulses in the brain. In recent years it has become clear that beta-amyloid exists in a variety of forms in the brain and that not all of its forms are equally toxic. For one thing, a longer form of beta-amyloid, designated amyloid beta 42, is known to be more toxic than the more common, shorter form, known as amyloid beta 40. The reason for this has to do with the tendency of beta-amyloid molecules to stick to each other, forming groups composed of two, three, four and even hundreds of individual beta-amyloid molecules (amyloid beta 42 is stickier). The largest of these groupings form the plaques found in the Alzheimer’s patient’s brain. Most importantly, is has been shown that the forms of beta-amyloid that are toxic, consist of groups rather than individual molecules.

The longer form of beta-amyloid, shown above as amyloid beta 42, is known to be more toxic than the shorter form, known as amyloid beta 40.

Dr. Dennis Selkoe and his colleagues at Harvard University recently removed beta-amyloid from the brains of deceased Alzheimer’s patients. He and his colleagues then exposed animal models to preparations containing different size groupings of beta-amyloid derived from the human brains. The researchers observed that the “dimers” of beta-amyloid (those groupings consisting of just two molecules of beta-amyloid) prevented the models from learning simple tasks.

The researchers also exposed the animal models’ brain tissue to the beta-amyloid groupings and found that it disrupted the normal transmission of signals between brain cells. These fascinating results will have to be repeated by other laboratories if “dimers” are to be accepted as the primary cause of the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Many scientists believe larger forms of beta-amyloid groupings will also be toxic and it is not yet certain which forms actually exist in the human brain. Nevertheless, the Harvard study is an important step forward.

These observations, and those of the Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research, are important because they suggest that scientists may be able to create drugs or treatments that inhibit formation of the specific, toxic beta-amyloid group(s). In addition to finding which groupings are toxic, the Fisher researchers are determining how the groupings work to disrupt brain cell communication. By answering this question, they can seek or develop treatments that prevent beta-amyloid from causing the damage to the brain that leads to Alzheimer’s.

Source: www.ALZinfo.org. Preserving Your Memory: The Magazine of Health and Hope; Fall 2008. Reviewed by William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Fisher Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University.

http://www.alzinfo.org/12/alz-guide/proteins-alzheimers-disease

Como explica el doctor Emilio Rodríguez Ferrón, jefe del servicio de Pediatría del Hospital Perpetuo Socorro de Alicante, el ser humano nace con un número de neuronas finito, más de cien mil millones que -a partir de ahí- se irán reduciendo hasta el fin de nuestros días.

Sin embargo, es durante los primeros años de vida cuando estas neuronas se organizan y comienzan a establecer conexiones entre ellas (las denominadas sinapsis) a una velocidad irrepetible. Además, aunque no crecerán nuevas células nerviosas, es durante la infancia cuando estás células se mielinizan: es decir, desarrollan completamente la mielina, la sustancia que las recubre y permite que establezcan conexiones unas con otras. "Sin mielina el impulso eléctrico no funciona bien", resume.

Por este motivo, Rodríguez Ferrón divide el desarrollo cerebral de la infancia en dos etapas. Desde el nacimiento hasta los tres años, explica este neuropediatra a ELMUNDO.es, es cuando el cerebro tiene su máxima plasticidad, las regiones cerebrales son capaces de adaptarse e incluso ejercer las funciones de otras regiones si éstas están dañadas por cualquier motivo.

Hasta los seis años, prosigue este especialista, "el cerebro sigue adquiriendo habilidades pero sobre una estructura anatómica ya definida"; de manera que a esa edad puede darse por concluido el proceso de desarrollo cerebral.

Pero no sólo las neuronas se desarrollan, se recubren de mielina y se conectan entre ellas (a los tres años habrán establecido 1.000 trillones de conexiones); también el aspecto del cerebro cambia en los primeros años de vida.

En primer lugar, y es lo que antes salta a la vista, crece en tamaño y se proporciona con el resto del cuerpo. El cerebro representa un tercio de todo nuestro organismo en el momento en que nacemos, y alcanzará casi el 80% de su tamaño adulto entre los cuatro y cinco años. Parte de ese crecimiento se debe a la propia mielina, que aumenta su volumen, así como a las neuronas, que se expanden para extender sus ramificaciones.

Como prosigue el neuropediatra de Alicante, también existen algunas diferencias entre la sustancia blanca de un niño y un adulto (en el primero ocupa menos espacio en el cerebro); mientras que en el caso de la sustancia gris, permanece prácticamente igual.

Precisamente, un estudio publicado en 2010 en la revista 'Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences' concluyó que las regiones cerebrales que más se desarrollan durante la infancia son las mismas que diferencian al ser humano de los primates.

Según explicaba el equipo de Terrie Inder, aunque todas las áreas cerebrales crecen a medida que este órgano madura, las que más se expanden son aquellas en las que tienen lugar las "funciones mentales más elevadas" (como el lenguaje o el pensamiento), es decir las regiones temporal lateral, parietal y frontal.

Y aunque no habían diseñado su trabajo para dar respuesta a esta pregunta, se atreven a aventurar que el retraso en el desarrollo físico de estas zonas puede deberse a la necesidad de limitar el tamaño del cerebro en el momento de nacer para que éste pueda pasar por el cuello del útero materno en el parto. O, simplemente, que sea una cuestión de prioridades: "Al nacer, la visión es vital porque el bebé la necesita para mamar y reconocer a su madre; mientras que otras funciones más desarrolladas no serán necesarias hasta que el niño vaya madurando".

Pero si alguien ha destacado en las últimas décadas a la hora de adentrarse en la mente de los niños, esa ha sido Elizabeth Spelke, de la Universidad de Harvard (EEUU), que lleva treinta años haciendo experimentos para demostrar que incluso los recién nacidos tienen una especie de 'conocimiento innato' a partir del cual desarrollamos el resto de nuestras habilidades.

Spelke ha demostrado que, entre esas capacidades que el cerebro infantil trae 'de serie' destaca una cierta capacidad numérica (bebés de sólo un mes son capaces de distinguir un grupo de cuatro sonidos de otro de 12); son conscientes de la solidez de los objetos o de que prefieren interactuar con personas que con objetos inmateriales.

Pero a pesar de todos estos avances, el cerebro sigue siendo un gran desconocido. De hecho, en EEUU, se lleva a cabo un experimento que evaluará desde su nacimiento hasta los 18 años a 564 niños de todo el país. Mediante imágenes de resonancia magnética, el proyecto Brain-Child, pretende estudiar cómo se desarrolla y organiza este misterioso órgano de traje gris.

El Mundo

For centuries, scientists had few clues about the inner workings of the brain. The three pounds of nerve tissue that give us our thoughts and memories remained stubbornly out of reach. But all that is changing rapidly. Advances in imaging are unlocking the mysteries of the hundred billion interconnected nerve cells that shape our personalities and consciousness. They are also providing vital insights into just what happens when things go terribly wrong—as in Alzheimer’s disease—to rob us of our memories and selves.

Most of the time, in about 9 cases out of 10, doctors use their clinical judgment, along with medical histories, memory exams, and brain scans, to correctly identify Alzheimer’s disease. But diagnosis often comes years after the disease starts, when Alzheimer’s has already done irreparable damage to the brain. And a definitive diagnosis still requires an autopsy, where pathologists can examine first-hand the telltale plaques and tangles that mar the brains of those with the disease.

An imaging device or other test to diagnose Alzheimer’s at an earlier stage, before grave damage has been done, could be key to effectively treating, or even curing, the disease when effective therapeutic measures become available. Such a test could identify people at risk even before memory loss and other symptoms arise, when drugs and other therapies may be most effective. It might also allow doctors to monitor people with the disease to determine whether new, experimental treatments are working.

“Early detection may be critical for slowing, or even halting, the relentless downward progression of Alzheimer’s,” says Nobel laureate Dr. Paul Greengard, director of The Fisher Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at The Rockefeller University in New York. “As we continue to unlock the basic underlying causes of the disease, it is vital that we come to understand the course of Alzheimer’s at its earliest stages.”

Mapping the Living Brain

We’ve come a long way since German physician Alois Alzheimer first peered into a light microscope a century ago to examine the shrunken brain of Auguste D., the middle-aged woman who died of the memory-robbing ailment that would later bear his name. There, magnified several hundred times, were the clumps of “senile plaque” that scientists would later identify as beta-amyloid, the toxic protein that builds up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Speckled throughout were also the string-like tangles composed of the substance we now call tau.

Today, scientists around the world are using advanced, computerized imaging techniques and complex molecular markers to delve into the secrets of the living brain. They can view the brain at a molecular level inconceivable in Dr. Alzheimer’s day, and assess what goes wrong in an illness like Alzheimer’s.

Scanning methods like CT (computed tomography) and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) can be used to identify minute structural changes in the brain. Researchers at Dartmouth Medical School recently used MRI, for example, to show that forgetful seniors have less gray matter, the outer brain layer crucial for thinking and memory, than their mentally alert peers.

A particularly promising form of MRI, called functional MRI, looks not just at brain structure but also at brain function. The technique can, for example, determine which parts of the brain are at work when we try to recall the name of our first-grade teacher or solve a long division problem. Studies are currently under way to determine if functional MRI can be combined with other imaging and genetic tests to identify patients at risk for future Alzheimer’s.

“As new therapies for Alzheimer’s disease enter the pipeline over the next five years, early diagnosis will become critical for patient selection,” says Dr. Jeffrey Petrella of Duke University. He recently completed a functional MRI study that found that a part of the brain that recalls personal memories may actually become uninhibited in people with incipient Alzheimer’s, impairing their ability to complete more focused everyday tasks.

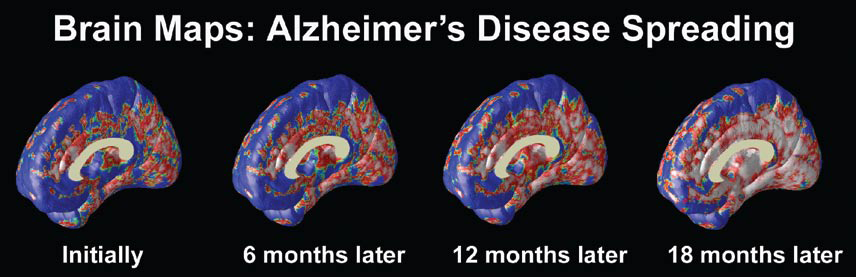

Figure 1: Damage to the brain in Alzheimer’s disease. - Time lapse brain scans show healthy brain activity (red and blue areas) and rapidly spreading areas of cell death (gray areas) in someone with Alzheimer’s disease. About 5 percent of brain cells die each year in someone with Alzheimer’s, compared to less than 1 percent in a senior who is aging normally.

A Window Into the Brain

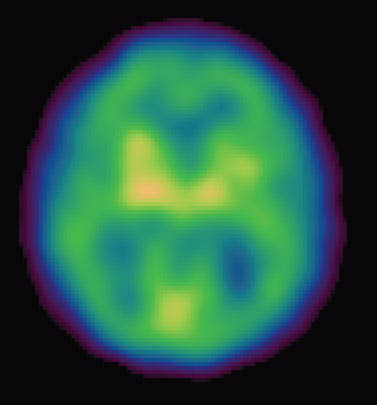

Other high-tech imaging techniques, like PET (positron emission tomography) and SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography), provide unique views into the living brain at work. Areas on the computer screen that light up red, for instance, may show parts of the brain that are actively absorbing a radioactive tracer, while blue areas may indicate brain areas that are dulled. Low activity in memory centers of the brain, for example, may detect Alzheimer’s at its earliest stages, years before symptoms such as forgetfulness appear.

Figure 2: Midline through the brain. - Alzheimer’s initially damages the brain’s temporal lobes (controlling memory), followed by the limbic system (the seat of emotions), then the frontal lobes (affecting self-control). The pattern of damage helps explain the sequence of thought and behavior problems that commonly arise as Alzheimer’s becomes more severe.

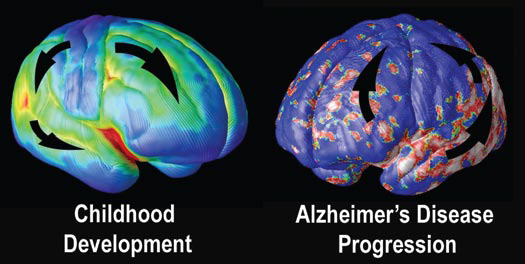

At the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), brain researcher Dr. Paul Thompson has created remarkable 3-D time-lapse images of brains affected by Alzheimer’s by overlaying images collected from various scanning techniques. Among the areas where cell death may first occur are in the hippocampus, the seahorse-shaped brain structures behind the ears that control memory processing. These are followed by other structures in the limbic system, affecting emotions, and by the frontal lobe areas that affect decision making and self-control.

“One of the diseases that really has a chance to be cured is Alzheimer’s,” says Dr. Thompson. “Imaging offers the opportunity to capture a detailed picture of what is going on in the brain of someone with Alzheimer’s over time. It can also tell you if the disease is being slowed down by a particular drug, or even by lifestyle factors like diet or exercise.”

A new imaging agent called Pittsburgh Compound B, developed at the University of Pittsburgh, is allowing doctors for the first time to visualize the buildup—or dissipation— of beta-amyloid in the living brain. The compound slips past the blood-brain barrier and attaches to plaque, where it appears as a brightly lit image on PET scans.

“For the first time, doctors may be able to tell definitively if treatment is working,” says Dr. Steven DeKosky, director of Pittsburgh’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. “If we can make a specific early diagnosis through imaging, then we can track the effectiveness of new drugs and other treatments as well.”

Another substance called FDDNP, developed at UCLA, attaches to plaques and tangles in the brain and is similarly visualized using PET scans. In a recent study, it proved very effective in distinguishing patients with mild cognitive impairment, a form of memory loss that often precedes Alzheimer’s.

Additional strategies are also under development. At the Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorders in New Haven, Conn., scientists are testing radioactive tracers in combination with SPECT to visualize the buildup of beta-amyloid plaque over time in people with early Alzheimer’s. Investigators also hope to test the response to treatment with vaccines and other treatments that may rid the brain of the toxic protein. Several other tracers targeting other brain proteins are in development with the goal of providing a more complete picture of brain changes that occur in AD.

A radioactive tracer that binds to amyloid shows the buildup of beta-amyloid plaque over time in people with early Alzheimer’s.

“Neuroimaging is a tool with extraordinary potential to gain a window into the brain chemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and to help to develop and monitor new therapies... enabling us to conduct the research important to both Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. Kenneth Marek, president and senior scientist, Institute for Neurodegenerative Disorder.

And at the University of Minnesota, doctors are studying a simple 60-second test called MEG (magnetoencephalography) that, like an EKG for the heart, measures magnetic fields emitted by the brain and which, in initial tests, detected early Alzheimer’s.

Although research on these and other techniques is just beginning, it may allow scientists to detect Alzheimer’s at its earliest stages, up to a decade or more before patients experience symptoms like memory loss.

Figure 3: Early brain development and Alzheimer’s. - The sequence of brain changes in Alzheimer’s is the exact opposite of how the brain develops during childhood. The last parts of the brain to mature, including the memory centers, are the most vulnerable in Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s “Fingerprints”

In addition to brain imaging, researchers have long sought to identify natural substances in the blood or body that distinguish Alzheimer’s from other forms of dementia. Scientists in New York are using cutting edge “proteomics” technology, which analyzes proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord.

“Just as the human genome reflects the array of genes a person possesses, the ‘proteome’ is the vast collection of proteins expressed by those genes,” explains Cornell University professor Dr. Kelvin Lee. Using detailed image analysis and complex computer and statistical analyses, he and colleagues have identified a group of 23 proteins in the spinal fluid that may be unique to Alzheimer’s disease and serve as a unique “fingerprint” that could one day lead to a test to diagnose Alzheimer’s at its earliest stages.

“You might have a promising treatment for the disease, but how can you know for sure that it’s impacting on the underlying pathology, rather than just easing outward symptoms, as most of the drugs that we have now do?” says Dr. Norman Relkin of Weill Cornell Medical College, who is involved in the current research. “We are hopeful that by monitoring changes in these cerebrospinal biomarkers, we can actually track the effectiveness—or lack thereof—of experimental drugs.”

At Stanford University, scientists recently identified a set of 18 proteins in the blood that may signal early Alzheimer’s and predict which patients with mild cognitive impairment go on to develop full-blown Alzheimer’s. Still, it will likely be several years before results are confirmed.

Other early screening tests, some surprisingly low-tech, are also being tested. In one recent report, people with poor memory who misidentified more than 2 of 10 common scents—strawberry, pineapple, lilac, clove, menthol, lemon, smoke, natural gas, soap, and leather— were five times more likely to progress to Alzheimer’s years later than those who retained their olfactory sense. This “sniff test” will require further confirmation, but in initial tests, it performed as well as memory exams and MRI scans in determining which people would go on to develop Alzheimer’s. Researchers speculate that the same processes that destroy brain cells vital for memory may also affect those crucial for scent. Other scientists are looking into a “skin test” that measures chemical changes in the skin that may signal early Alzheimer’s.

An ongoing public-private research collaboration called the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, is working with medical centers across north America to identify additional biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers will examine more than 800 men and women, ranging in age from 55 to 90, using PET scans, MRI, and blood and spinal fluid tests in an attempt to identify biomarkers that may be an early warning sign of Alzheimer’s.

“Earlier diagnosis means earlier treatment,” says the Fisher Center’s Dr. Greengard. “And the more we understand about the basic causes of Alzheimer’s, the closer we move to a cure.”

Figures 1, 2, 3 Courtesy of Dr. Paul Thompson, Professor of Neurology, UCLA School of Medicine

Source: www.ALZinfo.org. Author: Toby Bilanow, Preserving Your Memory: The Magazine of Health and Hope; Winter 2007.

http://www.alzinfo.org/11/alz-guide/visualizing-alzheimers

Reading, writing, doing crossword puzzles and solving challenging puzzles may be linked to a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Now a new study shows how mental stimulation may protect the brain.

The study, from researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, used brain scans and an imaging agent called Pittsburgh compound B to measure changes in the brains’ of test subjects. Pittsburgh compound B binds to beta-amyloid, a toxic protein that builds up in the brains of those with Alzheimer’s and is the main component of the brain plaques that characterize the disease.

The study, published in the Archives of Neurology, included 65 healthy older volunteers whose average age was 76, along with 10 seniors who had Alzheimer’s disease. Ten young people in their 20s and 30s served as controls.

Participants were asked about how often they engaged in mentally demanding activities like reading books or newspapers, writing letters or e-mails, going to the library and playing games. As part of the questionnaire, they were asked to rate how often they did these activities – ranging from every day or almost every day, to once a year or less – during five different periods of their lives: at age 6, 12, 18, 40 and currently.

The researchers found that the more often someone engaged in mentally stimulating activities, the less buildup of beta-amyloid they were likely to have in the brain.

“We report a direct association between cognitive activity and Pittsburgh compound B uptake, suggesting that lifestyle factors found in individuals with high cognitive engagement may prevent or slow deposition of beta-amyloid, perhaps influencing the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s disease,” the researchers write.

Engaging in mentally challenging tasks in the early and middle years seemed to be especially important for preventing the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaque, the researchers found. The brains of seniors who engaged in mentally stimulating activities most often were comparable to those of young people in the control group. Older people with the least cognitive stimulation, on the other hand, had brains that more closely resembled those of people with Alzheimer’s.

The study participants were also asked about how often they engaged in physical activities like cycling, waking, dancing or doing yoga in the previous two-weeks. Other studies have shown a link between physical activity and staying mentally sharp in old age, though that association was not demonstrated in this study. Those who were more physically active, though, tended to participate in mentally challenging tasks.

The authors note that Alzheimer’s is a complex disease, with many factors contributing to its onset and course. “Cognitive activity is just one component of a complex set of lifestyle practices linked to Alzheimer’s disease risk that may be examined in future work,” they concluded.

By ALZinfo.org, The Alzheimer's Information Site. Reviewed by William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Fisher Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University.

Source: Susan M. Landau; Shawn M. Marks; Elizabeth C. Mormino; et al: “Association of Lifetime Cognitive Engagement and Low β-Amyloid Deposition.” Archives of Neurology online doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.2748

Many people use a nicotine patch to help kick the smoking habit. But wearing a nicotine patch may also help to sharpen memory and thinking skills in those with mild cognitive impairment, a new study suggests.

Memory problems are a hallmark of mild cognitive impairment, a condition that sometimes progresses to full-blown Alzheimer’s. And nicotine is known to sharpen cognitive skills. Smokers who are given the drug, for example, do better on tests requiring attention skills. Some studies have suggested that nicotine – by patch or through injections – can boost memory in people with Alzheimer’s as well.

To test whether nicotine helps people with mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, researchers recruited 67 men and women with the condition. All were nonsmokers, and their average age was 76. Some wore a nicotine patch for six months, and others were a lookalike dummy patch. They were then given tests of memory and thinking.

Those who got the nicotine patch scored higher on tests of memory that required them to remember lists of words or what they read. They were also better able to pay attention and had faster reaction times. Those wearing the placebo patch, by contrast, did worse on these tests after six months. The patch, which was given at a dose of 15 milligrams per day, also appeared to be safe, with few side effects.

The researchers note that nerve cells involved in attention contain receptors for nicotine, which may in part explain the findings. People with Alzheimer’s disease show diminished nicotine receptors, though in those with MCI, the receptors are often intact.

One interesting finding was that nicotine appeared to have greater benefit in those who carried the APOE-E4 gene. People with this gene are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s, though carrying the gene does not mean you will get the disease.

Still, experts caution that it’s too soon to recommend that those with MCI start wearing a nicotine patch to help keep the memory sharp. The study was relatively small, so larger tests would need to be conducted to confirm the findings. It’s also not known how the patch might affect smokers or former smokers with memory problems. And one study in mice suggested that nicotine could lead to increased production of tau, a protein that builds up in the brains of those with Alzheimer’s.

Still, the scientists believe that the results provide strong justification for further research into the effects of nicotine on those with memory problems. They note that nicotine or similar drugs could be “a promising strategy to ameliorate symptoms of MCI and slow progression to dementia.”

By ALZinfo.org, The Alzheimer's Information Site. Reviewed by William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Fisher Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University.

Source: P. Newhouse, MD: K. Kellar, PhD; P. Aisen, MD; et al: “Nicotine Treatment of Mild Cognitive Impairment: A 6-Month Double-Blind Pilot Clinical Trial.” Neurology 2012, Vol. 78, pages 91-101.

People with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia are much more likely to be hospitalized for a range of illnesses than those without dementia, a new study finds. And in many cases, the hospitalizations could have been prevented.

The findings are concerning since a visit to the hospital is especially disorienting for anyone with dementia and can lead to disorientation, falls and other problems that complicate medical care. Even a short hospital visit may lead to a prolonged stay and hasten physical and cognitive decline in someone with Alzheimer’s disease.

“Nonelective hospitalization of older people, particularly those with dementia, is not a trivial event,” wrote the authors of a study from the University of Washington in Seattle. The findings appeared in The Journal of the American Medical Association.

For the study, the researchers focused on conditions that can sometimes be prevented with proper outpatient medical care and careful patient monitoring. They analyzed hospitalizations among more than 3,000 seniors who were part of the Adults Changes in Thought (ACT) study, none of whom had dementia at the start of the study period in 1994.

By the end of the study, in 2007, 494 participants had developed dementia, and 86 percent of them had been admitted to the hospital at least once. Among the 2,525 participants who didn’t have dementia, only 59 percent required hospital stays during the study period.

Among those with dementia, the average annual hospital admission rate was more than twice that of those without dementia. Hospitalizations for circulatory problems, genitourinary issues, infections, nerve disorders and respiratory problems were significantly higher among dementia sufferers compared with those without dementia.

Three conditions that can often be treated at home or the doctor’s office, without an overnight hospital stay, accounted for two-thirds of the hospitalizations that might have been prevented: bacterial pneumonia, congestive heart failure and urinary tract infections. Hospital admission rates for these conditions were much higher for those with dementia than those who didn’t have it.

Hospital admission rates for two other preventable complaints – dehydration and duodenal ulcers – were also higher for those with dementia than those without it.

Knowledge of preventable conditions that are likely to lead to hospitalization is important for family members, caregivers and doctors, who can work together to help prevent them from getting worse. Proactive, early management for these conditions and regular monitoring is especially important for those with Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, since hospital stays can be so difficult for these patients. The extent and quality of care at home is an important factor that can determine the success or failure of treating illnesses at home.

In an editorial that accompanied the study, Dr. Constantine G. Lyketsos of Johns Hopkins University writes that, “Physicians should participate in this effort by making detection of dementia in its early stages and implementation of dementia care a priority.” Major goals of dementia care, he notes, are to manage accompanying medical illnesses and taking steps to prevent them whenever possible from happening in the first place.

By ALZinfo.org, The Alzheimer's Information Site. Reviewed by William J. Netzer, Ph.D., Fisher Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation at The Rockefeller University.

Source: Elizabeth A. Phelan; Soo Borson; Louis Grothaus; Steven Balch; Eric B. Larson: “Association of Incident Dementia With Hospitalizations.” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 307 (2), Jan. 11, 2012, pages 165-172.

En los ensayos preliminares con humanos la vacuna demostró ser segura y no produjo efectos secundarios en los pacientes con Alzheimer.

Estos resultados, afirma la investigación publicada en The Lancet Neurology, allanan el camino para llevar a cabo ensayos clínicos más amplios para confirmar la efectividad del fármaco.

Si se comprueba su eficacia, dicen los expertos, será un avance muy importante en la búsqueda de una cura para esta enfermedad degenerativa que, según la Organización Mundial de la Salud, ya se convirtió en la mayor epidemia global.

Aunque no se sabe con precisión qué es lo que causa Alzheimer, se cree que la enfermedad es provocada por la acumulación de una proteína -llamada beta-amiloide- que en lugar de descomponerse, como ocurre normalmente, forma placas tóxicas en el cerebro causando daño y muerte celular.

Esto eventualmente provoca los problemas de memoria y otras incapacidades cognitivas que son los síntomas típicos de la enfermedad de Alzheimer.

Desde hace tiempo varios equipos de investigadores en todo el mundo están tratando de encontrar formas de prevenir la acumulación de esta sustancia.

Hace más de una década se probó por primera vez una vacuna, pero los resultados en humanos mostraron graves efectos adversos y el estudio fue suspendido.

Ahora, la nueva vacuna -llamada CAD 106- mostró por primera vez que sus efectos pueden ser bien tolerados por los humanos.

El fármaco actúa estimulando al sistema inmune para que desarrolle una respuesta de ataque contra la formación de la proteína amiloide en el cerebro.

"Este ensayo de seguridad es un primer paso muy importante. Ahora viene la verdadera prueba para descubrir si el tratamiento es efectivo para combatir la enfermedad de Alzheimer"

Dr. Simon Ridley

La investigación, dirigida por el profesor Bengt Winblad del Centro de Investigación de la Enfermedad de Alzheimer del Instituto Karolinska, en Estocolmo, involucró a 58 personas de entre 50 y 80 años.

Todos los individuos mostraban las primeras etapas de Alzheimer, de leve a moderado.

Los pacientes fueron divididos aleatoriamente en dos grupos: en uno recibieron tres inyecciones de la vacuna CAD 106 y en el otro tres inyecciones de un placebo.

Al final del ensayo de tres años, los análisis de sangre de los participantes mostraron que 80% de los participantes que habían recibido las inyecciones de CAD 106 tenían niveles más altos de anticuerpos, los cuales los habían protegido contra la formación de placas amiloides.

Según los investigadores, 56 participantes experimentaron efectos secundarios leves, como síntomas similares a los de un resfriado o una erupción en el sitio de la inyección.

Pero ninguno experimentó efectos secundarios graves vinculados al fármaco.

Tal como señalan los investigadores, estos resultados indican que el tratamiento "es seguro y bien tolerado" para uso en humanos y ahora deberán confirmarse sus efectos positivos en ensayos clínicos más amplios.

También deberá mostrarse si la vacuna, además de prevenir la formación de placas amiloides, puede mejorar las funciones cognitivas de los enfermos de Alzheimer.

Las investigaciones han mostrado que las placas amiloides comienzan a formarse antes de aparezcan los síntomas de la demencia.

Por lo tanto, afirman los expertos, cualquier tratamiento será más efectivo si es suministrado en las primeras etapas de la enfermedad.

"Este ensayo de seguridad es un primer paso muy importante", afirma el doctor Simon Ridley, jefe de investigación de la organización Alzheimer Research Uk.

"Ahora viene la verdadera prueba para descubrir si el tratamiento es efectivo para combatir la enfermedad de Alzheimer".

"Los ensayos clínicos amplios y de largo plazo determinarán si la CAD 106 puede ayudar a la memoria y capacidades cognitivas de las personas, además de reducir la cantidad de amiloide en el cerebro", agrega.

Encontrar un fármaco capaz de revertir o al menos detener los síntomas de Alzheimer y otras formas de demencia se ha convertido en asunto de urgencia para muchos científicos en todo el mundo.

Se calcula que actualmente unos 26 millones de personas sufren alguna forma de demencia en el mundo y se predice que la cifra se duplicará cada 20 años para alcanzar 81 millones en el 2040.

Revue is a research tool aimed at helping people with severe memory impairment including Alzheimer's disease. Revue takes photos unobtrusively when triggered by the internal sensors within the camera. If the internal sensors aren't triggered after a certain amount of time Revue will take a photo. Images are uploaded at the end of the user’s day or particular event such as a wedding, day trip or holiday.

TIME LAPSE VIDEO OF REVUE PHOTOS

SENSECAM

Revue is based on Microsoft’s SenseCam technology. Eye Witness recently reported how a person with severe memory impairment recalled events after using SenseCam.

El otro día emitieron un reportaje en las noticias en el que contaban algo sobre la utilización de dispositivos fotográficos para ayudar a las personas con Alzheimer. Se centraba en una investigación científica que se estaba llevando a cabo y que venía a concluir que el hecho de repasar cada día la actividad cotidiana, con la ayuda de fotografías tomadas automáticamente, facilitaba que los recuerdos quedaran fijados y no se olvidaran a las 24 horas, como les sucede a las personas que padecen de esta enfermedad.

La cámara que se veían en el reportaje parecía la ViconRevue desarrollada originalmente bajo el nombre de SenseCam por Microsoft; no es precisamente nueva y de hecho existen ya modelos mejorados respecto al original, un poco más baratos y con mayor calidad y capacidad que las primeras versiones. Con 8 GB puede almacenar unos 8 días completos de fotos (unas 20.000 imágenes a 3 Mpx, con un gran angular) y emplea diferentes sistemas inteligentes para tomar las fotos, en función de la luz, movimientos, etc.

Lo implacable de la Ley de Moore hará que en unos pocos años estos dispositivos sean cada vez más capaces y baratos; de hecho la ViconRevue es ya cara para los estándares actuales. No sería raro que viéramos modelos similares por menos de 100 euros y con capacidad de archivar un mes o más de fotografías en unos pocos años; lo mismo podría suceder con las imágenes en vídeo – por no hablar de que sería fácil subirlas a la red directamente. Si a eso se le añaden los avances en miniaturización y duración de la batería, en poco tiempo podríamos prácticamente convertirnos en cámaras de seguridad andantes, grabando todo aquello a lo que tenemos acceso. Aparte de esto, existen ya herramientas como las que utiliza Stephen Wolfram para digitalizar y analizar su vida segundo a segundo, con interesantes implicaciones prácticas.

Estoy convencido de que ese momento llegará algún día para todos nosotros, con todo lo que ello implica. Si dejamos volar un poco la imaginación y recurrimos a la ciencia-ficción, el escenario podría ser muy parecido al de la estupenda película The Final Cut (2004) con Robin Williams (en español: La memoria de los muertos). En ella los protagonistas llevan una especie de implantes llamados Zoe que básicamente graba todas sus vidas. El propósito en ese caso es un poco diferente: servir como registro multimedia completo de la vida de la persona, para realizar un artístico montaje para deleite de familiares durante el funeral. (Como suele suceder, esos avanzados implantes no están al alcance de todo el mundo, inicialmente sólo se los pueden permitir los ricos y son codiciados por casi todos los demás.)

Parte de la trama de la película ahonda en algunos de los problemas de estos dispositivos y sus dilemas éticos – definitivamente un tema apasionante. Pero volviendo a nuestro mundo real, a las cámaras de baja resolución que se pueden llevar colgadas del cuello y graban lo que sucede a lo largo del día, ya mismo podemos ser conscientes de algunos de los problemas y situaciones peculiares que estos inventos suponen. Como siempre, planteando más preguntas que respuestas:

¿Puede alguien grabar todo lo que ve sin permiso de las personas que van a ser fotografiadas? Parece claro que yendo por la calle así habría de ser aunque pueda haber excepciones la normativa varía mucho de un país a otro. ¿Se debería avisar a otras personas de que se están tomando fotografías suyas en un ambiente particular? (por ejemplo, en una casa) ¿Y si se usa vídeo, o se graba todo el audio del entorno, incluyendo las conversaciones telefónicas? Finalmente, y puestos a elucubrar, ¿podría alguien pedir «ser borrado» de esos archivos fotográficos si descubre que existen? ¿Servirían esas grabaciones como pruebas en un juicio si las personas que aparecen no han dado su consentimiento expreso para ser grabadas? ¿Puede existir siquiera el concepto de privacidad en un mundo así?

Como suele suceder, es el tradicional impulso de la tecnología el que abre más cuestiones de las que soluciona. Pero eso no quiere decir que con un poco de sentido común no puedan resolverse todos esos dilemas y detalles. Lo que indica la situación, desde otro punto de vista, es que cada vez más todo lo que hacemos va a ser menos privado y más público, y que quienes pretendan conservar su privacidad a toda costa lo van a tener cada vez más complicado.

No obstante, esto puede que no sea un problema: debido a la paradoja de la privacidad a la que nos ha acostumbrado la tecnología, puede que precisamente lo preferido por la gente sea más visibilidad y transparencia, aun a costa de la privacidad. Quizá ser grabados en todas partes y que lo que hacemos sea cada vez más público, más «buscable» y más permanente sea una ventaja: podemos querer repasar conversaciones, recordar lo que hicimos ciertos días o realizar un montaje artístico-cinematográfico con los mejores momentos de nuestras vidas. Quién sabe. De momento, a las personas con Alzheimer parece que les está ayudando a recuperar esos días de su vida, que sin rememorar serían borrados automáticamente por su cerebro, lo cual ya es todo un avance para ellos.

Actualización: Tal y como unos cuantos lectores nos han recordado (¡gracias a todos!) también en The Entire History of You, el tercer episodio de Black Mirror se plantean estos mismos dilemas. Altamente recomendable esa miniserie, dicho sea de paso.

El cerebro comienza teniendo muchas sinapsis, más de las que mantiene en la edad adulta. A medida que el cerebro se desarrolla, pasa a través de cambios dinámicos para perfeccionar su sistema de circuitos, acortar la distancia de las conexiones sinápticas que no tienen mucha actividad, y preservar las sinapsis más fuertes y activas. Este período, conocido como poda sináptica, es una parte clave del desarrollo normal del cerebro.

Los científicos desconocen cómo estas sinapsis son seleccionadas y podadas; sin embargo, la eliminación precisa de las sinapsis no utilizadas, y el fortalecimiento de aquellas que son más necesarias, es esencial para la función normal del cerebro. Muchos trastornos de la infancia, como la ambliopía (pérdida de la visión en un ojo), diversas formas de retraso mental, la epilepsia, y el autismo, pueden ser causa de un desarrollo anormal del cerebro.

Las microglías se originan en la médula ósea, y se activan para defender al cuerpo contra las infecciones. La activación de las microglías también tiene lugar ante enfermedades, como un accidente cerebrovascular, o la enfermedad de Alzheimer. No siempre está claro, sin embargo, si estas células causan la degeneración de las células cerebrales, o si son parte del proceso de recuperación del cerebro. Recientemente, varios grupos de investigación han sugerido que la activación de las microglías también está presente en el cerebro normal.

En el nuevo estudio, los científicos del laboratorio de la doctora Stevens, utilizaron el sistema visual de los ratones para estudiar la poda sináptica, un modelo que sufre grandes cambios y remodelaciones durante el desarrollo, y que posee un circuito bien definido y fácil de manipular. Los científicos identificaron neuronas que se proyectan desde el ojo, hasta un área del cerebro llamada el núcleo geniculado lateral (NGL), observando que las microglías reactivas contenían porciones de sinapsis de las neuronas identificadas.

Posteriormente, los investigadores analizaron si la cantidad de actividad neuronal en una sinapsis determina su eliminación por parte de las microglías. Para ello, se utilizó un medicamento para aumentar la actividad en las neuronas que se proyectan desde un ojo, hallando menos poda de sinapsis en la región del cerebro correspondiente, en comparación con el ojo sin tratar. Cuando se utilizó un fármaco para reducir la actividad, esto dio lugar a una poda mayor, en comparación con el ojo sin tratar.

Los investigadores creen que las microglías eliminan sinapsis, según el nivel de actividad de ésta. Este hecho puede estar directamente relacionado con la ambliopía -la pérdida de visión en un ojo (los niños con ambliopía utilizan preferentemente un ojo, y la visión del ojo menos usado se deteriora por la pérdida sinapsis y células).

Una investigación anterior había revelado que las proteínas implicadas en el sistema inmunológico se encuentran cerca de las sinapsis, durante el desarrollo cerebral, y son necesarias para la poda. Para averiguar si estas mismas proteínas son utilizadas por las microglías para dar forma a las conexiones neuronales, los investigadores interrumpieron la vía de proteínas que se encuentra en las células inmunitarias del cerebro. Los resultados indican que estas proteínas provocan que las microglías corten sinapsis, y sugieren que las vías del sistema inmune son clave para una poda sináptica adecuada.

Stevens afirma que el estudio arroja luz sobre el papel de las microglías en el cerebro normal, y apoya nuevas investigaciones sobre las microglías en un contexto de enfermedad cerebral